- Home

- Charles Bukowski

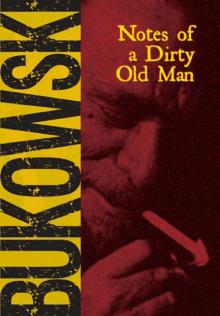

Notes of a Dirty Old Man

Notes of a Dirty Old Man Read online

NOTES OF A DIRTY OLD MAN

by Charles Bukowski

City Lights Books

San Francisco

NOTES OF A DIRTY OLD MAN

Copyright © 1969 by Charles Bukowski

All Rights Reserved

Cover design by Rex Ray

Cover photograph of Charles Bukowski by Brad Darby

Reproduced by courtesy of Brad Darby

Typography by Harvest Graphics

ISBN: 0-87286-074-4 / 978-0-87286-074-2

LC #73-84226

Visit our website: www.citylights.com

CITY LIGHTS BOOKS are edited by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Nancy J. Peters and published at the City Lights Bookstore, 261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133.

FOREWORD

More than a year ago John Bryan began his underground paper OPEN CITY in the front room of a small two story house that he rented. Then the paper moved to an apartment in front, then to a place in the business district of Melrose Ave. Yet a shadow hangs. A helluva big gloomy one. The circulation rises but the advertising is not coming in like it should. Across in the better part of town stands the L.A. Free Press which has become established. And runs the ads. Bryan created his own enemy by first working for the L.A. Free Press and bringing their circulation from 16,000 to more than three times that. It’s like building up the National Army and then joining the Revolutionaries. Of course, the battle isn’t simply OPEN CITY vs. FREE PRESS. If you’ve read OPEN CITY, you know that the battle is larger than that. OPEN CITY takes on the big boys, the biggest boys, and there are some big ones coming down the center of the street, NOW, and real ugly big shits they are, too. It’s more fun and more dangerous working for OPEN CITY, perhaps the liveliest rag in the U.S. But fun and danger hardly put margarine on the toast or fed the cat. You give up toast and end up eating the cat.

Bryan is a type of crazy idealist and romantic. He quit, or was fired, he quit and was fired — there was a lot of shit flying — from his job at the Herald-Examiner because he objected to them airbrushing the cock and balls off of the Christ child. This on the cover of their magazine for the Christmas issue. “And it’s not even my God, it’s theirs,” he told me.

So this strange idealist and romantic created OPEN CITY. “How about doing us a weekly column?” he asked off-handedly, scratching his red beard. Well, you know, thinking of other columns and other columnists, it seemed to me to be a terribly drab thing to do. But I started out, not with a column but a review of Papa Hemingway by A. E. Hotchner. Then one day after the races, I sat down and wrote the heading, NOTES OF A DIRTY OLD MAN, opened a beer, and the writing got done by itself. There was not the tenseness or the careful carving with a bit of a dull blade, that was needed to write something for The Atlantic Monthly. Nor was there any need to simply tap out a flat and careless journalism (er, journalesé??). There seemed to be no pressures. Just sit by the window, lift the beer and let it come. Anything that wanted to arrive, arrived. And Bryan was never a problem. I’d hand him some copy — in the early days — and he’d flit through it and say, “OK, it’s in.” After a while I’d just hand him copy and he wouldn’t read it; he’d just jam it into a cubbyhole and say, “It’s in. What’s going on?” Now he doesn’t even say, “It’s in.” I just hand him the copy and that’s that. It has helped the writing. Think of it yourself: absolute freedom to write anything you please. I’ve had a good time with it, and a serious time too, sometimes; but I felt mainly, as the weeks went on, that the writing got better and better. These are selections from about fourteen months worth of columns.

For action, it has poetry beat all to hell. Get a poem accepted and chances are it will come out 2 to 5 years later, and a 50-50 shot it will never appear, or exact lines of it will later appear, word for word, in some famous poet’s work, and then you know the world ain’t much. Of course, this isn’t the fault of poetry; it is only that so many shits attempt to print and write it. But with NOTES, sit down with a beer and hit the typer on a Friday or a Saturday or a Sunday and by Wednesday the thing is all over the city. I get letters from people who have never read poetry, mine or anybody else’s. People come to my door — too many of them really — and knock to tell me that NOTES OF A DIRTY OLD MAN turns them on. A bum off the road brings in a gypsy and his wife and we talk, bullshit, drink half the night. A long distance telephone operator from Newburgh, N.Y., sends me money. She wants me to give up drinking beer and to eat well. I hear from a madman who calls himself “King Arthur” and lives on Vine Street in Hollywood and wants to help me write my column. A doctor comes to my door: “I read your column and I think that I can help you. I used to be a psychiatrist.” I send him away.

I hope that these selections help you. If you want to send me money, o.k. Or if you want to hate me, o.k. too. If I were the village blacksmith you wouldn’t fuck with me. But I am just an old guy with some dirty stories. Writing for a newspaper, which, like me, might die tomorrow morning.

It’s all very strange. Just think, if they hadn’t airbrushed the cock and balls off the Christ child, you wouldn’t be reading this. So, be happy.

Charles Bukowski

1969

NOTES OF A DIRTY OLD MAN

some son of a bitch had held out on the money, everybody claiming they were broke, card game finished, I was sitting there with my buddy Elf, Elf was screwed-up as a kid, all shriveled, he used to lay in bed for years squeezing these rubber balls, doing crazy exercises, and when he got out of bed one day he was as wide as he was tall, a muscled laughing brute who wanted to be a writer but he wrote too much like Thomas Wolfe and, outside of Dreiser, T. Wolfe was the worst American writer ever born, and I hit Elf behind the ear and the bottle fell off the table (he’d said something that I disagreed with) and as the Elf came up I had the bottle, good scotch, and I got him half on the jaw and part of the neck under there and he went down again, and I felt on top of my game, I was a student of Dostoevski and listened to Mahler in the dark, and I had time to drink from the bottle, set it down, fake with a right and lend him the left just below the belt and he fell against the dresser, clumsily, the mirror broke, it made sounds like a movie, flashed and crinkled and then Elf landed one high on my forehead and I fell back across a chair and the thing flattened like straw, cheap furniture, and then I was in deep — I had small hands and no real taste for fighting and I hadn’t put him away — and he came on in like some zany two-bit vengeful individual, and I got in about one for three, not very good ones, but he wouldn’t quit and the furniture was breaking everywhere, very much noise and I kept hoping somebody would stop the damned thing — the landlady, the police, God, anybody, but it went on and on and on, and then I didn’t remember.

when I awakened the sun was up and I was under the bed. I got out from under and found that I could stand up. large cut under chin. scraped knuckles. I’d had worse hangovers. and there were worse places to awaken, like jail? maybe. I looked around. it had been real. everything broken and smeared and shattered, spilled — lamps, chairs, dresser, bed, ashtrays — gored beyond all measure, nothing sensible, everything ugly and finished. I drank some water and then walked to the closet. it was still there: tens, twenties, fives, the money I had thrown into the closet each time I had gone to piss during the card game, and I remembered starting the fight about the MONEY. I gathered up the green, placed it in my wallet, put my paper suitcase on the slanting bed and began to pack my few rags: laborer’s shirts, stiff shoes with holes in the bottom, hard and dirty stockings, lumpy pants with legs that wanted to laugh, a short story about catching crabs at the San Francisco Opera House, and a torn Thrifty Drugstore dictionary — “palingenesis — recapitulation of ancestral stages in life-history.”

t

he clock was working, the old alarm clock, god bless it, how many times had I looked at it on 7:30 a.m. hangover mornings and said, fuck the job? FUCK THE JOB! well, it said 4 p.m. I was just about to put it into the top of my suitcase when — sure, why not? — there was a knock on my door.

YEAH?

MR. BUKOWSKI?

YEAH? YEAH?

I WANT TO COME IN AND CHANGE THE SHEETS.

NO, NOT TODAY. I’M SICK TODAY.

OH, THAT’S TOO BAD. BUT JUST LET ME COME IN AND CHANGE THE SHEETS. THEN I’LL GO AWAY.

NO, NO, I’M TOO SICK, I’M JUST TOO SICK. I DON’T WANT YOU TO SEE ME THE WAY I AM.

it went on and on. she wanted to change the sheets. I said, no. she said, I want to change the sheets. on and on. that landlady. what a body. all body. everything about her screamed BODY BODY BODY. I’d only been there 2 weeks. there was a bar downstairs. people would come to see me, I wouldn’t be in, she’d just say, “he’s in the bar downstairs, he’s always in the bar downstairs.” and the people would say, “God and Jesus, man, who’s your LANDLADY?”

but she was a big white woman and she went for these Filipinos, these Filipinos did tricks man, things no white men would ever dream of, even me; and these Flips are gone now with their George Raft pulldown widebrims and padded-shoulders; they used to be the fashion leaders, the stiletto boys; leather heels, greasy evil faces — where have you gone?

well, anyhow, there was nothing to drink and I sat there for hours, going crazy; jumpy, I was, gnatz, lumpy balls, there I sat with $450 easy money and I couldn’t buy a draft beer. I was waiting for darkness. darkness, not death. I wanted out. another shot at it. I finally got the nerve up. I opened the door a bit, chain still on, and there was one, a little Flip monkey with a hammer. when I opened the door, he lifted the hammer and grinned. when I closed the door he took the tacks out of his mouth and pretended to pound them into the rug of the stairway leading to the first floor and the only door out. I don’t know how long it went on. it was the same act. everytime I’d open the door he’d lift the hammer and grin. shit monkey! he just stayed on the top step. I began to go crazy. I was sweating, stinking; little circles whirling whirling whirling, light flanks and flashes of light in my dome. I really felt like I was going to go screwy. I walked over and got the suitcase. it was easy to carry. rags. then I took the typewriter. a steel portable borrowed from the wife of a once-friend and never returned. it had a good solid feel: gray, flat, heavy, leery, banal. the eyes whirled to the rear of my head and the chain was off the door, and one hand with suitcase and one hand with stolen typewriter I charged into machinegun fire, the mourning morning sunrise, cracked-wheat crinkles, the end of all.

HEY! WHERE YOU GO?

the little monkey began to raise to one knee, he raised the hammer, and that’s all I needed — the flash of electric light on hammer — I had the suitcase in the left hand, the portable steel typer in the right, he was in perfect position, down by my knees and I swung with great accuracy and some anger, I gave him the flat and heavy and hard side, greatly, along the side of his head, his skull, his temple, his being.

there was almost a shock of light like everything was crying, then it was still. I was outside, suddenly, sidewalk, down all those steps without realization. like luck, there was a yellow cab.

CABBY!

I was inside. UNION STATION.

it was good, the quiet sound of tires in the morning air. NO, WAIT, I said. MAKE IT THE BUS DEPOT.

WHATZ MATTA, MAN? the cabby asked.

I JUST KILLED MY FATHER.

YO KILLED YO FATHA?

YOU EVER HEARD OF JESUS CHRIST?

SHORE.

THEN MAKE IT: BUS DEPOT.

I sat in the bus depot for an hour waiting for the bus to New Orleans. wondering if I had killed the guy. I finally got on with typewriter and suitcase, jamming the typewriter far into the overhead rack, not wanting the thing to fall on my head. it was a long ride with much drinking and some involvement with a redhead from Fort Worth. I got off at Fort Worth too, but she lived with her mother and I had to get a room, and I got a room in a whorehouse by mistake. all night the women hollering things like, “HEY! you’re not going to stick THAT thing in ME for ANY kind of money!” toilets flushing all night. doors opening and closing.

the redhead, she was a nice innocent thing, or bargained for a better man. anyhow, I left town without getting into her pants. I finally made New Orleans.

but the Elf. remember? the guy I fought in my room. well, during the war he was killed by machinegun fire. I’ve heard he lay in bed a long time, 3 or 4 weeks before he went. and the strangest thing, he had told me, no, he had asked me “suppose some STUPID son of a bitch puts his finger to a machinegun and cuts me in half?”

“then, it’s your fault.”

“well, I know you ain’t going to die in front of any god damned machinegun.”

“you’re sure as shit right, I ain’t, babe. unless it’s one of Uncle Sam’s.”

“don’t give me that crap! I know you love your country. I can see it in your eyes! love, real love!”

that’s when I hit him the first time.

after that, you’ve got the rest of the story.

when I got to New Orleans I made sure I wasn’t in any whorehouse, even though the whole town looked like one.

________

we were sitting in the office after dropping another one of those 7 to 1 ballgames, and the season was halfway over and we were in the cellar, 25 games out of first place and I knew that it was my last season as manager of the Blues. our leading hitter was batting .243 and our leading home run man had 6. our leading pitcher stood at 7 and 10 with an e.r.a. of 3.95. old man Henderson pulled the pint out of the desk drawer, took his cut, shoved the bottle at me.

“on top of all this,” said Henderson, “I even caught the crabs about 2 weeks ago.”

“jesus, sorry, boss.”

“you won’t be calling me boss much longer.”

“I know, but no manager in baseball can pull these rummies out of last place,” I said, knocking off a third of a pint.

“and worse,” said Henderson, “I think it was my wife who gave me the crabs.”

I didn’t know whether to laugh or what, so I kept quiet.

there was a most delicate knock on the office door and then it opened. and here stood some nut with paper wings glued to his back.

it was a kid about 18. “I’m here to help your club,” said the kid.

he had on these big paper wings. a real nut. holes cut in his suit. the wings are glued to his back. or strapped. or something.

“listen,” said Henderson, “will you please get the hell out of here! we’ve got enough comedy on the field now, just playing it straight. they laughed us right out of the park today. now, get out and fast!”

the kid reached over, took a slug from the pint, set it down and said, “Mr. Henderson, I am the answer to your prayers.”

“kid,” said Henderson, “you’re too young to drink that stuff.”

“I’m older than I look,” said the kid.

“and I got somethin’ that will make you a little older!” Henderson pressed the little button under his desk. that meant Bull Kronkite. I ain’t sayin’ the Bull has ever killed a man but you’ll be lucky to be smoking Bull Durham out of a rubber asshole when he gets through with you. the Bull came in almost taking one of the hinges off the door as he entered.

“which ONE, boss?” he asked, his long stupid fingers twitching as he looked about the room.

“the punk with the paper wings,” said Henderson.

the Bull moved in.

“don’t touch me,” said the punk with the paper wings.

the Bull rushed in, AND SO HELP ME GOD, that punk began to FLY! he flapped around the room, up near the ceiling. Henderson and I both reached for the pint but the old man beat me to it. the Bull dropped to his knees:

“LORD IN HEAVEN, HAVE MERCY ON ME! AN ANGEL! AN ANGEL!”

“don’t be a jerk!” said the angel, flapping around, “I’m no angel. I just want to help the Blues. I been a Blues fan ever since I can remember.”

“all right. come on down. let’s talk business,” said Henderson.

the angel, or whatever it was, flew on down and landed in a chair. the Bull ripped off the shoes and stockings of whatever it was and started kissing its feet.

Henderson leaned over and in a very disgusted manner spit into the Bull’s face: “fuck off, you subnormal freak! anything I hate is such sloppy sentimentality!”

the Bull wiped off his face and left very quietly.

Henderson flipped through the desk drawers.

“shit, I thought I had me some contract papers in here somewhere!”

meanwhile, while looking for the contract papers he found another pint and opened that. he looked at the kid while ripping off the cellophane:

“tell me, can you hit an inside curve? outside? how about the slider?”

“god damned if I know,” said the guy with the wings, “I been hiding out. all I know is what I read in the papers and see on TV but I’ve always been a Blues fan and I’ve felt very sorry for you this season.”

“you been hidin’ out? where? a guy with wings can’t hide out in an elevator in the Bronx! what’s your hype? how’ve you made it?”

“Mr. Henderson, I don’t want to bore you with all the details.”

“by the way, what’s your name, kid?”

“Jimmy. Jimmy Crispin. J.C. for short.”

“hey, kid, what the fuck you tryin’ to do, get funny with me?”

“oh no, Mr. Henderson.”

“then shake hands!”

they shook.

“god damn, your hands is sure COLD! you had anything to eat lately?”

“I had some french fries and beer with chicken about 4 p.m.”

“have a drink, kid.”

Henderson turned to me. “Bailey?”

“yeh?”

“I want the full friggin’ ballteam down on that field at 10 a.m. tomorrow morning. no exceptions. I think we’ve got the biggest thing since the a-bomb. now let’s all get outa here and get some sleep. you got a place to sleep, kid?”

Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame

Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame Factotum

Factotum Absence of the Hero

Absence of the Hero Notes of a Dirty Old Man

Notes of a Dirty Old Man Mockingbird Wish Me Luck

Mockingbird Wish Me Luck Beerspit Night and Cursing

Beerspit Night and Cursing Ham on Rye: A Novel

Ham on Rye: A Novel Tales of Ordinary Madness

Tales of Ordinary Madness The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship

The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship The Pleasures of the Damned

The Pleasures of the Damned Come on In!

Come on In! Screams From the Balcony

Screams From the Balcony The Most Beautiful Woman in Town & Other Stories

The Most Beautiful Woman in Town & Other Stories New Poems Book 3

New Poems Book 3 Hot Water Music

Hot Water Music What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire

What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way

The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way The Roominghouse Madrigals: Early Selected Poems, 1946-1966

The Roominghouse Madrigals: Early Selected Poems, 1946-1966 Living on Luck

Living on Luck Pulp

Pulp You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense

You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense Post Office: A Novel

Post Office: A Novel The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems

The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems Hollywood

Hollywood Run With the Hunted: A Charles Bukowski Reader

Run With the Hunted: A Charles Bukowski Reader Storm for the Living and the Dead

Storm for the Living and the Dead South of No North

South of No North More Notes of a Dirty Old Man: The Uncollected Columns

More Notes of a Dirty Old Man: The Uncollected Columns On Drinking

On Drinking On Love

On Love The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses

The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Play the Piano

Play the Piano Betting on the Muse

Betting on the Muse Women

Women The Most Beautiful Woman in Town

The Most Beautiful Woman in Town The Captain Is Out to Lunch

The Captain Is Out to Lunch Ham On Rye

Ham On Rye New Poems Book Three

New Poems Book Three The Roominghouse Madrigals

The Roominghouse Madrigals Post Office

Post Office The People Look Like Flowers At Last

The People Look Like Flowers At Last