- Home

- Charles Bukowski

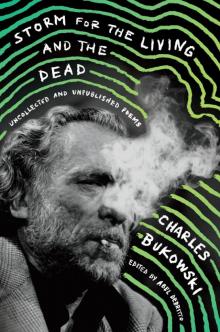

Storm for the Living and the Dead

Storm for the Living and the Dead Read online

disclaimer

Publisher’s Note

Rendering poetry in a digital format presents several challenges, just as its many forms continue to challenge the conventions of print. In print, however, a poem takes place within the static confines of a page, hewing as close as possible to the poet’s intent, whether it’s Walt Whitman’s lines stretching to the margin like Route 66, or Robert Creeley’s lines descending the page like a string tie. The printed poem has a physical shape, one defined by the negative space that surrounds it—a space that is crafted by the broken lines of the poem. The line, as vital a formal and critical component of the form of a poem as metaphor, creates rhythm, timing, proportion, drama, meaning, tension, and so on.

Reading poetry on a small device will not always deliver line breaks as the poet intended—with the pressure the horizontal line brings to a poem, rather than the completion of the grammatical unit. The line, intended as a formal and critical component of the form of the poem, has been corrupted by breaking it where it was not meant to break, interrupting a number of important elements of the poetic structure—rhythm, timing, proportion, drama, meaning, and so on. A little like a tightrope walker running out of rope before reaching the other side.

There are limits to what can be done with long lines on digital screens. At some point, a line must break. If it has to break more than once or twice, it is no longer a poetic line, with the integrity that lineation demands. On smaller devices with enlarged type, a line break may not appear where its author intended, interrupting the unit of the line and its importance in the poem’s structure.

We attempt to accommodate long lines with a hanging indent—similar in fashion to the way Whitman’s lines were treated in books whose margins could not honor his discursive length. On your screen, a long line will break according to the space available, with the remainder of the line wrapping at an indent. This allows readers to retain control over the appearance of text on any device, while also indicating where the author intended the line to break.

This may not be a perfect solution, as some readers initially may be confused. We have to accept, however, that we are creating poetry e-books in a world that is imperfect for them—and we understand that to some degree the line may be compromised. Despite this, we’ve attempted to protect the integrity of the line, thus allowing readers of poetry to travel fully stocked with the poetry that needs to be with them.

—Dan Halpern, Publisher

Contents

cover

title page

disclaimer

caught again at some impossible pass

in this—

why are all your poems personal?

prayer for broken-handed lovers

fast pace

I think of Hemingway

I was shit

corrections of self, mostly after Whitman:

the bumblebee

warble in

a trainride in hell

same old thing, Shakespeare through Mailer—

the rope of glass

tough luck

sometimes when I feel blue I listen to Mahler

men’s crapper

like a flyswatter

take me out to the ball game

I thought I was going to get some

charity ward

like that

phone call from my 5-year-old daughter in Garden Grove

the solar mass: soul: genesis and geotropism:

hooked on horse

fuck

2 immortal poems

T.H.I.A.L.H.

the lesbian

a poem to myself

fact

blues song

fat upon the land

love song

poem for Dante

the conditions

29 chilled grapes

burning in water, drowning in flame

a cop-out to a possible immortality:

well, now that Ezra has died . . .

warts

my new parents

something about the action:

55 beds in the same direction

b

finger

the thing

Bob Dylan

“Texsun”

warm water bubbles

a corny poem

the ladies of the afternoon

tongue-cut

Venice, Calif., nov. 1977:

mirror

head jobs

chili and beans

go to your grave cleanly—

kuv stuff mox out

a long hot day at the track

the letters of John Steinbeck

and the trivial lives of royalty never excited me either . . .

letter to a friend with a domestic problem:

agnostic

clones

gnawed by dull crisis

I been working on the railroad . . .

the way it goes

alone in a time of armies

going modern

it doesn’t always work

I have this room

a man for the centuries

dear old dad

peace and love

the world of valets

I live to write and now I’m dying

rip it

Henry Miller and Burroughs

family tree

being here

the only life

stomping at the Savoy

the glory days

congrats, Chinaski

he went for the windmills, yes

all my friends

a reader writes

ow said the cow to the fence that linked

my America, 1936

1/2/93 8:43 PM

musings

storm for the living and the dead

cover charge

good stuff

now

quit before the sun

#1

song for this softly-sweeping sorrow . . .

sources

acknowledgments

about the authors

also by charles bukowski

credits

copyright

about the publisher

caught again at some impossible pass

and the one with big feet, stupid, would not move

when I passed thro the aisle; that night at the barn

dance Elmer Whitefield lost a tooth fighting big

Eddie Green;

we’ll get his radio and we’ll get his watch, they said,

pointing at me, damn Yankee; but they didn’t know

I was an insane poet and I leaned there drinking wine

and loving all their women

with my eyes, and they were frightened and cowed

as any small town cattle

trying to figure out how to kill me

but first

foolishly

needing a reason; I could have told them

how not so long ago

I had almost killed for lack of reason;

instead, I took the 8:15 bus

to Memphis.

in this—

in this, grows the word of arrow;

we ache all through with simple terror

while walking down a simple street

and see where the tanks have piled it up:

faces run through, apples live with worms

to a squeeze of love; or out there—

where the sailors drowned, and the sea

washed it up, and your dog sniffed

and ran as if his hinds had been bitten

by the devil.

in this, say that Dylan wept

or Ezra craw

led with Muss

through thin Italian hours

as my fine brown dog

forgot the devil

or cathedrals shaking in sunlight’s gunfire,

and found love easily

upon the street outside.

in this, it’s true: that which makes iron

makes roses makes saints makes rapists

makes the decay of a tooth and a nation.

in this, a poem could be absence of word.

the smoke that once came up to push ten tons of steel

now lies flat and silent in an engineer’s hand.

in this, I see Brazil in the bottom of my glass.

I see hummingbirds—like flies, dozens of them—

stuck in a golden net. HELL!!—I have died in Words

like a man on a narcotic of thinning nectar!

in this, like blue through blue without bacchanalia dreams

where the tanks have piled it up, big boys shoot pool,

elf-eyes through smoke and waiting:

A CRACK AND BALLS, THAT’S ALL, ISN’T IT?

and courses in definitive literature.

why are all your poems personal?

why are all your poems personal? she

said, no wonder she hated you . . .

which one? I said. you know

which one . . . and don’t ever leave

water in your sink again, and you

can’t broil a roast; my landlady said

you’re very handsome and she wanted to

know why we didn’t get together

again . . .

did you tell her?

could I tell her you’re conceited

and alcoholic? could I tell her about

the time I had to pick you up

off your back

when you had that fight?

could I tell her

you play with yourself?

could I tell her

you think

you’re Mr. Vanbilderass?

why don’t you go home?

I’ve always loved you, you know

I’ve always loved you!

good. some day I’ll write a poem about

it. a very personal

poem.

prayer for broken-handed lovers

in dwarfed and towering rage, in ambulances of hate,

stamping out the ants, stamping out the sleepless ants

forevermore . . . pray for my horses, do not pray for me;

pray for the fenders of my car, pray for the carbon on

the filaments of my brain . . . exactly, and listen,

I do not need any more love, any more wet stockings

like legs of death crawling my face in a midnight’s

bathroom . . . make me sightless of blood and wisdom and

despair, don’t let me see the drying carnation

pinking-out against my time, buttonholed and rootless

as the tombs of memory;

well, I’ve been bombed out of

better places than this, I’ve had the sherry shaken

out of my hand, I’ve seen the teeth of the piano move

filled with explosions of rot; I’ve seen the rats in

the fireplace

leaping like rockets through the flames;

pray for Germany, pray for France, pray for Russia,

do not pray for me . . . and yet . . . and yet I can see again

the crossing of the lovely legs, of more sherry and more

disappointment, more bombs—surging seas of bombs,

my paintings flying like birds amongst the earrings

and bottles, amongst the red lips, amongst the love letters

and the last piano, I will cry that I was right: we

never should have been.

fast pace

I came in awful tired with a finger sliced off and frost

on my feet and the lightning coming down the wallpaper;

they hung three men in the streets and the mayor was drunk

on candy, and they sunk the friggin’ fleet and the vultures

were smoking Havana cigars; o.k., I see where some bathing

beauty sliced her left wrist an’ they found her in a comatose

state in her bedroom—probably pining her heart out for

me, but I’ve got to move out of town: I thought I was a

no-sweat kid, a rock, but I just found a

grey hair above my

left ear.

I think of Hemingway

I think of Hemingway sitting

in a chair, he had a typewriter

and now he no longer touches

his typewriter, he has no more

to say.

and now Belmonte has no more

bulls to kill, sometimes I think

I have no more poems to write,

no more women to love.

I think of the form of the poem

but my feet hurt, there is dirt

on the windows.

the bulls sleep nights in the

fields, they sleep good without

Belmonte.

Belmonte sleeps good without

Belmonte but I do not sleep

so well.

I have neither created nor

loved for some time, I swat

at a fly and miss, I am an

old grey dog growing tooth-

less.

I have a typewriter and now

my typewriter no longer has

anything to say.

I will drink until morning

finds me in bed with the

biggest whore of them all:

myself.

Belmonte & Poppa, I under-

stand, this is the way it

goes, truly.

I have watched them bring

the dirt down all morning

to fill the holes in the

streets. I have watched

them put new wires on

the poles, it rained

last night, a very

dry rain, it was

not a bombing, only the

world is ending and I am

unable to write

about it.

I was shit

grief, the walls are bloody with grief and who cares?

a sparrow, a princess, a whore, a bloodhound?

by god, dirt cares, dirt, and dirt I shall be,

I’ll score a hero’s blast where heroes are all the same:

Ezra packed next to gopher just as I,

just as I, the faint splash of rain in the empty brain,

o by god, the noble intentions, the lives, the sewers,

the tables in Paris

flaunting and floating in our swine memories,

Havana, Cuba, Hemingway

falling to the floor

blood splashing all exits.

if Hemingway kills himself

what am I?

if Cummings dies across his typewriter,

if Faulkner clutches his heart and goes,

what am I?

what am I? what was I

when Jeffers died in his tomb,

his stone cocoon?

I was shit, shit, shit, shit.

I now fall to the floor and raise the last of myself

what’s left of myself

I promise grails filled with words as well as wine,

and the green, and the shade flapping,

all this is nothing,

God shaving in my bathroom,

rent due,

lightning breaking the backs of ants,

I must close in upon myself,

I must stop playing tricks for

deep inside

somewhere

above the nuts or

below or in that head

not yet crushed

eyes looking out like damned and impossible fires,

I see the gap I must leap, and I will be strong

>

and I will be kind, I have always been kind,

animals love me as if I were a child crayoning

the edges of the world,

sparrows walk right by, flies crawl under my eyelids,

I cannot hurt anything

but myself,

I cannot even in the bloody grief

scream;

this is more than a scripture inside my brain—

I am tossed along the avenues of trail and trial

like dice

the gods mouthing their fires of strength

and I

must not die,

yet.

corrections of self, mostly after Whitman:

I would break the boulevards like straws

and put old rattled poets who sip milk

and lift weights

into the drunk tanks from Iowa

to San Diego;

I would announce my own firm intention to immortality

quietly

since nobody would listen anyway,

and I would break the Victrola

I would break the soul of Caruso

on a warm night full of flies;

I would go hymie-ass

shifting it up the boulevards

on an old Italian racing bike,

glancing backwards

always knowing

like goodnights in Germany

or gloves thrown down,

it happens.

I would cry for the armies of Spain,

I would cry for Indians gone to wine,

I would cry, even, for Gable dead

if I could find a tear;

I would write introductions to books of poetry

of young men gone half-daft

with the word;

I would kill an elephant with a bowie knife

to see his trunk fall

like an empty stocking.

I would find things in sand and things

under my bed: teeth-marks, arm-marks, signs,

tips, paint-stains, love-stains, scratchings

of Swinburne . . .

I would break the mountains for their olive pits,

I would keen dead-nosed divers

with ways to go,

and as it happens

I would swat and kill one more fly

or write

one more useless poem.

the bumblebee

she dressed like a bumblebee,

black stripes on yellow,

and clish clish slitch went

the gun, the gun was always there,

Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame

Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame Factotum

Factotum Absence of the Hero

Absence of the Hero Notes of a Dirty Old Man

Notes of a Dirty Old Man Mockingbird Wish Me Luck

Mockingbird Wish Me Luck Beerspit Night and Cursing

Beerspit Night and Cursing Ham on Rye: A Novel

Ham on Rye: A Novel Tales of Ordinary Madness

Tales of Ordinary Madness The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship

The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship The Pleasures of the Damned

The Pleasures of the Damned Come on In!

Come on In! Screams From the Balcony

Screams From the Balcony The Most Beautiful Woman in Town & Other Stories

The Most Beautiful Woman in Town & Other Stories New Poems Book 3

New Poems Book 3 Hot Water Music

Hot Water Music What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire

What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way

The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way The Roominghouse Madrigals: Early Selected Poems, 1946-1966

The Roominghouse Madrigals: Early Selected Poems, 1946-1966 Living on Luck

Living on Luck Pulp

Pulp You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense

You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense Post Office: A Novel

Post Office: A Novel The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems

The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems Hollywood

Hollywood Run With the Hunted: A Charles Bukowski Reader

Run With the Hunted: A Charles Bukowski Reader Storm for the Living and the Dead

Storm for the Living and the Dead South of No North

South of No North More Notes of a Dirty Old Man: The Uncollected Columns

More Notes of a Dirty Old Man: The Uncollected Columns On Drinking

On Drinking On Love

On Love The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses

The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Play the Piano

Play the Piano Betting on the Muse

Betting on the Muse Women

Women The Most Beautiful Woman in Town

The Most Beautiful Woman in Town The Captain Is Out to Lunch

The Captain Is Out to Lunch Ham On Rye

Ham On Rye New Poems Book Three

New Poems Book Three The Roominghouse Madrigals

The Roominghouse Madrigals Post Office

Post Office The People Look Like Flowers At Last

The People Look Like Flowers At Last