- Home

- Charles Bukowski

Storm for the Living and the Dead Page 8

Storm for the Living and the Dead Read online

Page 8

I found myself flying to this other

state to see her—twice. and

each time noticing

more men’s heads about her

apartment.

“who’s this guy?” I asked her

about one of them.

“oh, that’s Billyboy, the bronco

rider . . .”

I left 2 or 3 days

later . . .

lives continued and 2 or 3 women later

my friend Jack Bahiah came by. we

talked of this and that, then Jack

mentioned that he had flown out to

see the sculptress.

“did she do your head, Jack?”

“yeah, man, she did my head but it

didn’t look like me, man. guess who

it looked like, man?”

“I dunno, man . . .”

“it looked like you . . .”

“Jack, my man, you always had a great line

of shit . . .”

“no shit, man, no shit . . .”

Jack and I drank much wine that night, he’s

pretty good at pouring it down.

“I was holding her in my arms in the bed

and she said, ‘God, I love him, Jack, I

miss him!’ and then she started crying.”

I didn’t hate him at all for fucking her

for sleeping against her when I had slept

against her for 5 or 6 years, and that shows

the durability of humans: we can roust it

out and punch it down and forget it.

I know that she’s still sculpting men’s

heads and can’t stop. she once told me

that Rodin did something similar in a

slightly different way. all right.

I wish her the luck of the clay and

the luck of the men. it’s been a long

night into noon, sometimes, for most

of us.

chili and beans

hang them upside down through the plentiful

night,

burn their children and molest their crops,

cut the throats of their wives,

shoot their dogs, pigs and servants;

whatever you don’t kill, enslave;

your politicians will make you heroes,

courts of international law will rule

your victims guilty;

you will be honored, given medals,

pensions, villas along the river

with your choice of pre-prostitute

women;

the priests will open the doors of God

to you.

the important thing is victory,

it always has been;

you will be ennobled,

you will be promoted as the humble and

gracious conqueror

and you will believe it.

what it means is that the human mind

is not yet ready

so you will claim a victory for the

human spirit.

a cut throat can’t answer.

a dead dog can’t bite.

you’ve won.

proclaim the decency.

go to your grave cleanly—

nobody cares

nobody really cares

didn’t you know?

didn’t you remember?

nobody really cares

even those footsteps

walking toward somewhere

are going nowhere

you may care

but nobody cares—

that’s the first step

toward wisdom

learn it

and nobody has to care

nobody is supposed to care

sexuality and love are flushed away

like shit

nobody cares

learn it

belief in the impossible is the

trap

faith kills

nobody cares—

the suicides, the dead, the gods

or the living

think of green, think of trees, think

of water, think of luck and glory of a

sort

but cut yourself short

quickly and finally

of depending upon the love

or expecting the love of

another

nobody cares.

kuv stuff mox out

gunned down outside the Seaside Motel I stand looki

ng at the live lobster in a fishshop on the Redondo

Beach pier the redhead gone to torture other males

it’s raining again it’s raining again and again som

etimes I think of Bogart and I don’t like Bogart an

y more kuv stuff mox out—when you get a little mon

ey in the bank you can write down anything on the p

age call it Art and pull the chain gunned down in a

fish market the lobsters you see they get caught lik

e we get caught. think of Gertie S. sitting there

telling the boys how to get it up. she was an ocea

n liner I prefer trains pulling boxcars full of gun

s underwear pretzels photos of Mao Tse-tung barbell

s kuv stuff mox out—(write mother) when you flower

my stone notice the fly on your sleeve and think of

a violin hanging in a hockshop. many hockshops hav

e I been gunned down in best one in L.A. they pull

a little curtain around he who wishes to hock and h

e who might pay something. it’s an Art hockshops a

re needed like F. Scott Fitz was needed which makes

us pause this moment: I like to watch live lobster

s they are fire under water hemorrhoids—gross othe

r magic—balls!: they are lobsters but I like to w

atch them when I if I should get rich I will get a

First page of the first 10-page draft.

large glass tank say ten feet by four by four and I

’ll sit and watch them for hours while drinking the

white moselle I am drinking now and when people com

e by I will chase them away like I do now. I mean,

some people say change means growth well certain per

manent acts also prevent decay like flossing fuckin

g fencing fatting belching and bleeding under a hun

dred watt General Electric bulb. novels are nice m

ice are fussy and my lawyer tells me that Abraham L

incoln did some shit that never got into the histor

y books—which makes it the same wall up and down.

never apologize. understand the sorrow of error. b

ut never. don’t apologize to an egg a serpent a lo

ver. gunned down in a green taxi outside Santa Cru

z with an AE-I in my lap grifted in the pickpocket’

s hand slung like a ham. was it Ginsberg did a may

pole dance in Yugoslavia to celebrate May D

ay catch me doing that and you can cut both my back

pockets off. you know I never heard my mother piss

. I’ve heard many women piss but now that I think

of it I can’t ever remember hearing my mother piss.

I am not particular about planets I don’t dislike t

hem I mean like peanut shells in an ashtray that’s

planets. sometimes every 3 or 4 years you see a fa

ce it is usually not the face of a child but that f

ace makes an astonishing day even though the light

is in a certain way or you were driving by in an a

utomobile or you were walking and the face was movi

ng past in a bus or an auto it make that day of the

moment like a brain-jolt something to tell you it’s

always solitary being gunned down while slipping a

stick

of gum out of the wrapper outside Hollywood’s

oldest pool parlor on the west side of Western belo

w the boulevard. the gross is net and the net is g

ross and Gertie S. never showed her knees to the bo

ys and Van Gogh was a lobster a roasted peanut. I

think that “veer” is a splendid word and it’s still

raining gunned down in water waterbags worth of pig

’s snouts cleverly like cigarettes for men and for

women I care enough to proclaim liberty throughout

the land then wonder why nuns are nuns butchers tha

t and fat men remind me of glorious things breathin

g dust through their hems. if I gunned down Bogar

t he’d spit out his cigarette grab his left side in

black and white striped shirt look at me through a

butterfat eye and drop. if meaning is what we do w

e do plenty if meaning isn’t what we do check squar

e #9 it probably falls halfway in between which sus

tains balance and the poverty of the poor and fire

hydrants mistletoe big dogs on big lawns behind iron

fences. Gertie S., of course, was more interested

in the word than the feeling and that’s clearly fai

r because men of feeling (or women) (or) (you see)

(how nice) (I am) usually become creatures of Actio

n who fail (in a sense) and are recorded by the peo

ple of words whose works usually fail not matter. (

how nice). roll and roll and roll it keeps raining

gunned down in a fish market by an Italian with bad

breath who never knew I fed my cat twice a day and

never masturbated while he was in the same room. no

w you know in this year of 1978 I paid $8441.32 to

the government and $2419.84 to the State of Califor

nia because I sat down to this typewriter usually d

runk after the horse races and I don’t even use a ma

jor commercial publisher and I used to live off of

one nickel candy bar a day typewriter in hock I pri

nted my stuff with a pen and it came back. I mean,

fellow dog, men sometimes turn into movies. and som

etimes movies can get to be not so good. pray for

me. I don’t apologize. cleverness is not the out

endurance helps if you can hit the outside spiker

at 5:32 twilight—bang! the Waner brothers used to

bat two three for the Pirates now only 182 people i

n Pittsburgh remember them and that’s exactly proper

. what I didn’t like about that Paris gang was tha

t they made too much of writing but nobody can say

that they didn’t get it down as well as possible wh

en all the heads and eyes seemed to be looking else

where that’s why in spite of all the romanticism at

tached I go along not for the propaganda but for th

e sillier reasons of luck and the way. my lobsters

horses and lobsters and white moselle and there’s a

good woman near me after all of the bad or the seem

ing bad. Rachmaninoff is on now on the radio and I

finish my second bottle of moselle. what a lovely

emotional hound he was my giant black cat stretched

across the rug the rent is paid the rain has stoppe

d there is a stink to my fingers my back hurts gunn

ed down I fall roll those lobsters examine them the

re’s a secret there they hold pyramids drop them al

l the women of the past all the avenues doorknobs bu

ttons falling from shirt I never heard my mother pi

ss and I never met your father I think that we’d ha

ve drunk enough, properly.

a long hot day at the track

out at the track all day burning in the sun

they turned it all upside down, sent in all

the longshots. I only had one winner, a 6

to one shot. it’s on days like that you notice

the hoax is on.

I was in the clubhouse. I usually meet the

maître d’ of Musso’s in the clubhouse. that

day I met my doctor. “where the hell you been?”

he asked me. “nothing but hangovers lately,”

I told him. “you come by anyhow. you don’t

have to be sick. we’ll have lunch. I know a

Thai place, we’ll eat Thai food. you still

writing that porno stuff?” “yeah,” I said,

“it’s the only way I can make it.” “let me

sit with you,” he said, “I’ve got the 6.”

“I’ve got the 6 too,” I said, “that means

we’re fucked.”

we sat down and he told me about his four

wives: the first one didn’t want to copulate.

the second wanted to go skiing at

Aspen all the time. the third one was

crazy. the fourth one was all right, they’d

been together seven years.

the horses came out of the gate. the doctor

just looked at me and talked about his fourth

wife. he was some talking doctor. I used to

get dizzy spells listening to him as I sat on

the edge of the examination table. but he had

brought my child into the world and he had sliced

out my hemorrhoids.

he went on about his fourth wife . . .

the race was 6 furlongs and unless it’s a pack

of slow maidens 6 furlongs are usually run

somewhere between one minute and nine or ten

seconds. the one horse was 24 to one and had

jumped out to a three length lead. the son of

a bitch looked like he had no intention of

stopping.

“look,” I said, “aren’t you going to watch

the race?”

“no,” he said, “I can’t stand to watch, it

upsets me too much.”

he began on his fourth wife again.

“hold it,” I said, “they’re coming down the

stretch!”

the 24 to one had 5 lengths at the wire. it

was over.

“there’s no logic to any of this stuff out here,”

said the doctor.

“I know,” I said, “but the question I want you to

answer is: ‘why are we out here?’”

he opened his wallet and showed me a photo of

his two children. I told him that they were very

nice children and that there was one race left.

“I’m broke,” he said, “I’ve got to go. I’ve lost

$425.”

“all right, goodbye.” we shook hands.

“phone me,” he said, “we’ll eat at the Thai place.”

the last race wasn’t any better: they ran in a

9 to one shot who was stepping up in class and

hadn’t won a race in two years.

I went down the escalator with the losers. it

was a hot Thursday in July. what was my doctor

doing at the racetrack on a Thursday? suppose

I’d had cancer or the clap? Jesus Christ, you

couldn’t trust anybody anymore.

I’d read in the paper in between races

where these kids had busted into this

house and had beaten a 96-year-old woman

to death and had almost beaten to death

her 82-year-old blind sister or daughter,

I didn’t remember. but they had taken a

color television set.

I thought, if they catch me out here

tomorrow I deserve to lose. I’m not

going to be h

ere, I don’t think I

will.

I walked toward my car with the next

day’s Racing Form curled up in my

right hand.

the letters of John Steinbeck

I dreamt I was freezing and when I woke up and found out

I wasn’t freezing I somehow shit the bed.

I had been working on the travel book that night and

hadn’t done much good and they were taking my horses

away, moving them to Del Mar.

I’d have time to be a writer now. I’d wake up in the

morning and there the machine would be looking at me,

it would look like a tarantula; not so—it would look

like a black frog with fifty-one warts.

you figure Camus got it because he let somebody else

drive the car. I don’t like anybody else driving the

car, I don’t even like to drive it myself. well,

after I cleaned the shit off I put on my yellow

walking shorts and drove to the track. I parked and

went in.

the first one I saw was my biographer. I saw him

from the side and ducked. he was cleanly-dressed,

smoked a pipe and had a drink in his hand.

last time over at my place he gave me two books:

Scott and Ernest and The Letters of John Steinbeck.

I read those when I shit. I always read when I shit

and the worse the book the better the bowel movement.

then after the first race my doctor sat down beside me.

he looked like he had just gotten out of surgery and

hadn’t washed very well. he stayed until after the

8th race, talking, drinking beer and eating hot dogs.

then he started in about my liver: “you drink so god

damned much I want to take a look at your liver. you

come see me now.” “all right,” I said, “Tuesday after-

noon.”

I remembered his receptionist. last time I had been there

the toilet had overflowed and she had got down on the floor

on her knees to wipe it up and her dress had pulled up

high above her thighs. I had stood there and watched,

telling her that Man’s two greatest inventions had been

the atom bomb and plumbing.

Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame

Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame Factotum

Factotum Absence of the Hero

Absence of the Hero Notes of a Dirty Old Man

Notes of a Dirty Old Man Mockingbird Wish Me Luck

Mockingbird Wish Me Luck Beerspit Night and Cursing

Beerspit Night and Cursing Ham on Rye: A Novel

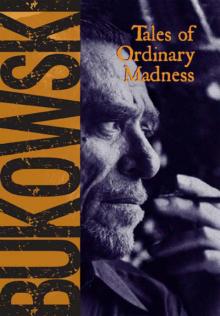

Ham on Rye: A Novel Tales of Ordinary Madness

Tales of Ordinary Madness The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship

The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship The Pleasures of the Damned

The Pleasures of the Damned Come on In!

Come on In! Screams From the Balcony

Screams From the Balcony The Most Beautiful Woman in Town & Other Stories

The Most Beautiful Woman in Town & Other Stories New Poems Book 3

New Poems Book 3 Hot Water Music

Hot Water Music What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire

What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way

The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way The Roominghouse Madrigals: Early Selected Poems, 1946-1966

The Roominghouse Madrigals: Early Selected Poems, 1946-1966 Living on Luck

Living on Luck Pulp

Pulp You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense

You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense Post Office: A Novel

Post Office: A Novel The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems

The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems Hollywood

Hollywood Run With the Hunted: A Charles Bukowski Reader

Run With the Hunted: A Charles Bukowski Reader Storm for the Living and the Dead

Storm for the Living and the Dead South of No North

South of No North More Notes of a Dirty Old Man: The Uncollected Columns

More Notes of a Dirty Old Man: The Uncollected Columns On Drinking

On Drinking On Love

On Love The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses

The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Play the Piano

Play the Piano Betting on the Muse

Betting on the Muse Women

Women The Most Beautiful Woman in Town

The Most Beautiful Woman in Town The Captain Is Out to Lunch

The Captain Is Out to Lunch Ham On Rye

Ham On Rye New Poems Book Three

New Poems Book Three The Roominghouse Madrigals

The Roominghouse Madrigals Post Office

Post Office The People Look Like Flowers At Last

The People Look Like Flowers At Last